What Factors Affect Nuclear Stability and Binding Energy?

Nuclear stability and the binding energy curve are key topics that describe why atomic nuclei display varying levels of stability and how energy trends arise due to nuclear forces. Understanding these concepts is fundamental for analyzing mass defect, energy release in nuclear reactions, and predicting the behavior of different isotopes in physics.

Nuclear Stability: Factors Influencing Stability

The stability of a nucleus depends mainly on the balance between attractive strong nuclear forces and repulsive electrostatic forces among protons. Stable nuclei are characterized by specific combinations of protons (Z) and neutrons (N), where the nuclear force overcomes Coulomb repulsion.

For light nuclei, stability generally occurs when the proton and neutron numbers are approximately equal. In heavier nuclei, more neutrons than protons are needed for stability due to increasing proton-proton repulsion. The proton-neutron ratio and nuclear shell effects further influence stability.

The presence of magic numbers and pairing of nucleons enhance stability for certain nuclei. This aspect is addressed in nuclear structure analysis such as Nuclear Structure Composition.

Mass Defect and Nuclear Binding Energy

When nucleons combine to form a nucleus, the total mass of the nucleus is less than the sum of the individual masses of protons and neutrons. This difference is termed the mass defect ($\Delta m$), which results from the energy released as nucleons bind together.

The mass defect is related to binding energy ($BE$) by Einstein’s equation $BE = \Delta m \times c^2$, where $c$ is the speed of light. This binding energy is the energy required to separate a nucleus into its individual protons and neutrons.

In practice, binding energy is often calculated in MeV using $1\ \text{u} = 931.5\ \text{MeV}/c^2$. The mass defect in atomic mass units is given by $\Delta m = [Z(m_{_p}) + N(m_{_n}) - M(A,Z)]$, where $Z$ and $N$ are the number of protons and neutrons, and $M(A,Z)$ is the actual mass of the nucleus.

Further reading on energy interactions in nuclei is found at Binding Energy.

Binding Energy per Nucleon and Its Importance

Binding energy per nucleon ($\dfrac{BE}{A}$) is a key parameter in nuclear physics and is defined as the total binding energy divided by the mass number, $A$. This value measures the average energy binding each nucleon within the nucleus.

A higher binding energy per nucleon indicates a more stable nucleus. Stability increases as the binding energy per nucleon rises, reaching a maximum for nuclei like iron-56, beyond which it typically decreases with increasing mass number.

Binding Energy Curve: Features and Interpretation

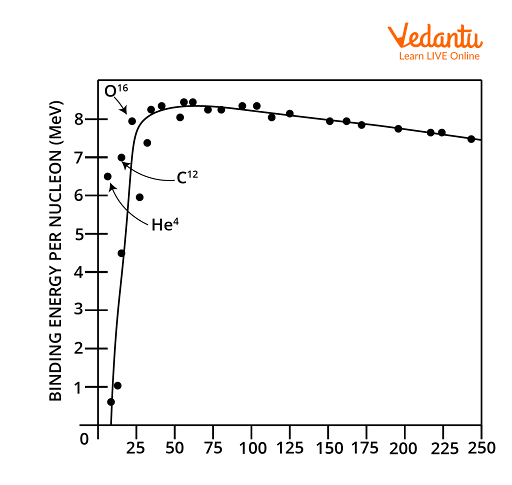

The binding energy per nucleon curve is a graph of $\dfrac{BE}{A}$ versus mass number $A$. It reveals key patterns about nuclear stability across different elements and isotopes.

- Steep rise for light nuclei (A < 20)

- Maximum binding near iron (A ≈ 56, BE/A ≈ 8.8 MeV)

- Gradual decline for heavy nuclei (A > 60)

Nuclei lying at the curve’s peak, such as iron and nickel, are exceptionally stable and do not readily undergo nuclear reactions. Nuclei with mass numbers far from the peak display lower stability and can participate in fusion or fission phenomena.

Link between Binding Energy and Nuclear Stability

The nuclear binding energy curve directly connects to nuclear stability. The higher the binding energy per nucleon, the greater is the cohesion among nucleons and the higher the nucleus's stability. Iron-56 exemplifies maximum stability by being at the curve’s apex.

Heavy nuclei (A > 60), with lower binding energy per nucleon, are susceptible to fission. Light nuclei, with even lower values, can undergo fusion. This concept underpins the physics of nuclear power and stellar energy generation, as detailed in Nuclear Fission And Fusion.

Calculation Example: Binding Energy and Stability of Helium-4

Consider the He-4 nucleus. Data: Z = 2, N = 2. Atomic mass = 4.0026 u. Mass of 2 protons = $2 \times 1.00728 = 2.01456$ u. Mass of 2 neutrons = $2 \times 1.00866 = 2.01732$ u.

Total mass of separate nucleons = $2.01456 + 2.01732 = 4.03188$ u. Mass defect $\Delta m = 4.03188\ \text{u} - 4.0026\ \text{u} = 0.02928$ u. Binding energy $BE = 0.02928 \times 931.5 = 27.26$ MeV.

Binding energy per nucleon = $27.26 \div 4 = 6.8$ MeV. This value is lower than the peak for iron-56, so helium-4 is stable but less so than elements at the maximum of the binding energy curve.

Summary Table: Key Nuclear Stability and Binding Energy Facts

| Quantity | Formula/Value |

|---|---|

| Mass Defect ($\Delta m$) | (Sum of nucleon masses) − (Nucleus mass) |

| Binding Energy (BE) | $\Delta m \times 931.5$ |

| Binding Energy per Nucleon ($BE/A$) | $BE \div A$ |

| Unit for BE | MeV |

| Most Stable Nucleus | Iron-56 (BE/A ≈ 8.8 MeV) |

Nuclear Reactions and the Binding Energy Curve

Energy release in nuclear reactions is explained by movements along the binding energy curve. Fusion of light nuclei (moving up the curve) and fission of heavy nuclei (moving down toward the peak) both result in products with higher binding energy per nucleon, releasing energy. These processes are the foundational principles behind Nuclear Reactor operations.

Pitfalls to Avoid in Calculations

Errors often occur by confusing total binding energy with binding energy per nucleon. Always divide the total binding energy by the total number of nucleons to accurately compare nuclear stability. Use consistent units such as MeV and u in calculations.

Refer to precise atomic mass data, and ensure conversion factors like $1\ \text{u} = 931.5\ \text{MeV}$ are correctly applied. Decimal errors or incorrect mass values can lead to significant mistakes.

Further Applications and Related Concepts

Understanding the binding energy curve is essential to topics such as radioactive decay, nuclear transformations, and isotopic stability. These aspects are also explored in Alpha, Beta, And Gamma Decay.

The concept further connects with quantum phenomena relevant to nuclear physics, such as those presented in Dual Nature Of Matter.

FAQs on Understanding Nuclear Stability and the Binding Energy Curve

1. What is nuclear stability and how is it related to the binding energy curve?

Nuclear stability is the tendency of a nucleus to remain unchanged, and it is closely linked to the binding energy curve. The binding energy curve shows the average energy per nucleon for different nuclei, revealing that nuclei with higher binding energy per nucleon are more stable.

Key points:

- Nuclear stability increases with higher binding energy per nucleon.

- The curve peaks at iron (Fe-56), indicating maximum stability.

- Nuclei lighter or heavier than iron are less stable and can undergo fusion or fission, respectively, to reach a more stable state.

2. Why is iron considered the most stable nucleus on the binding energy curve?

Iron (especially Fe-56) has the highest binding energy per nucleon on the binding energy curve, making it the most stable nucleus.

Reasons include:

- Maximum nuclear stability due to optimal proton-neutron ratio.

- Requires the most energy to break apart each nucleon.

- Fusion of lighter nuclei and fission of heavier nuclei both move towards forming nuclei like iron for greater stability.

3. How does the binding energy per nucleon change across the periodic table?

The binding energy per nucleon increases sharply for light nuclei, peaks around iron, and then decreases gradually for heavier nuclei.

Variation pattern:

- Low for light elements (e.g., hydrogen, helium)

- Rises steeply up to mid-weight elements (especially iron)

- Decreases slowly for heavier elements (like uranium)

- This pattern explains the processes of nuclear fusion and fission in stars and nuclear reactors.

4. What happens to nuclear stability at the extremes of the binding energy curve?

Nuclei at the low and high extremes of the binding energy curve are less stable compared to mid-mass nuclei.

- Light nuclei (left side): Less stable, can undergo fusion to form heavier, more stable nuclei.

- Heavy nuclei (right side): Less stable, can undergo fission to split into smaller, more stable nuclei.

- Both processes release energy due to movement toward higher binding energy per nucleon.

5. What is binding energy and why is it important in nuclear physics?

Binding energy is the energy needed to break a nucleus into its individual protons and neutrons. It is crucial because it determines nuclear stability.

Importance includes:

- Measures the strength of the nuclear force holding nucleons together.

- Calculates the energy released in nuclear reactions like fusion and fission.

- Helps predict which isotopes are stable or radioactive.

6. How does the concept of mass defect relate to binding energy?

Mass defect is the difference between the mass of a nucleus and the total mass of its individual nucleons. This lost mass is converted to binding energy according to Einstein’s equation (E=mc²).

Relation:

- The mass defect directly measures the binding energy of the nucleus.

- Greater mass defect, higher binding energy, and greater stability.

7. What trends in binding energy per nucleon explain why both nuclear fusion and fission release energy?

Nuclear fusion and fission release energy because both move nuclei toward higher binding energy per nucleon.

- Fusion: Light nuclei combine, increasing binding energy per nucleon (move up the curve).

- Fission: Heavy nuclei split, their fragments have higher binding energy per nucleon (move up the curve from the right).

- Both processes lead to more stable nuclear configurations and release excess energy as heat or radiation.

8. What factors affect the stability of a nucleus?

Nuclear stability is affected by several factors, including:

- Proton-neutron ratio: Stable nuclei have specific ratios, as shown on the binding energy curve.

- Binding energy per nucleon: Higher binding energy equals higher stability.

- Magic numbers: Nuclei with certain numbers of protons or neutrons (2, 8, 20, 28, 50, 82, 126) are more stable.

- The presence of odd or even nucleons also impacts stability; even-even nuclei are generally more stable.

9. Explain the significance of the binding energy curve in understanding nuclear reactions.

The binding energy curve is vital for predicting which nuclear reactions can release energy.

Significance includes:

- Determines whether fusion (light elements) or fission (heavy elements) will be exothermic.

- Helps identify the most stable nuclei.

- Explains why stars perform fusion and why reactors use fission.

10. What is the relevance of the curve of binding energy in the CBSE syllabus for nuclear physics?

The binding energy curve is a key concept in the CBSE nuclear physics syllabus as it explains the principles behind stability, radioactivity, fusion, and fission.

It helps students:

- Understand fundamental nuclear properties.

- Analyze energy generation processes in stars and reactors.

- Solve typical exam questions regarding energy calculations and nuclear reactions.

11. What is the mass defect and how does it relate to binding energy?

Mass defect is the difference between the sum of the masses of individual nucleons and the measured mass of the nucleus. This deficit is converted into binding energy that holds the nucleus together.

- Greater mass defect indicates a more stable and strongly bound nucleus.

- Binding energy can be found using the mass defect and Einstein’s equation: E = mc².

12. Why are nuclei with magic numbers exceptionally stable?

Nuclei with magic numbers of protons or neutrons (2, 8, 20, 28, 50, 82, 126) are more stable because these configurations completely fill nuclear shells, similar to how noble gases fill electron shells.

- Magic numbers represent closed-shell configurations with strong binding.

- This leads to increased stability and less tendency to decay.