Molecular Basis of Inheritance- Key Notes for NEET Biology

Molecular Basis of Inheritance is an important chapter in NEET Biology that explains how traits are passed from parents to offspring. It covers the structure of DNA, the role of RNA in protein production, and processes like replication (how DNA copies itself), transcription (making RNA from DNA), and translation (building proteins from RNA). By understanding these core ideas, you will be better prepared to answer both basic and complex questions in the NEET exam. Vedantu’s notes simplify these topics so you can grasp them quickly and strengthen your preparation.

The DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid)

DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid) is the genetic material in most living organisms, while certain viruses (e.g., Tobacco Mosaic Virus) use RNA as their genetic material. RNA usually functions as a messenger, an adapter and can also act as a catalyst. The length of a DNA molecule is based on its number of base pairs (bp) or nucleotides. For instance-

Human (haploid) DNA- 3.3 × 10^9 bp

Bacteriophage φX174- 5386 nucleotides

Bacteriophage λ- 48502 bp

E. coli- 4.6 × 10^6 bp

Key Discoveries and Experiments

1869 (Friedrich Miescher)- Identified DNA in the cell nucleus and named it “nuclein.”

1928 (Frederick Griffith)- Showed that a “transforming principle” from heat-killed S-strain Streptococcus pneumoniae could make the non-virulent R-strain virulent.

Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod, and Maclyn McCarty- They determined that DNA is the biochemical basis of Griffith’s transforming principle.

1952 (Hershey and Chase)- Used radioactive labeling of bacteriophages to confirm that DNA, not protein, is the genetic material.

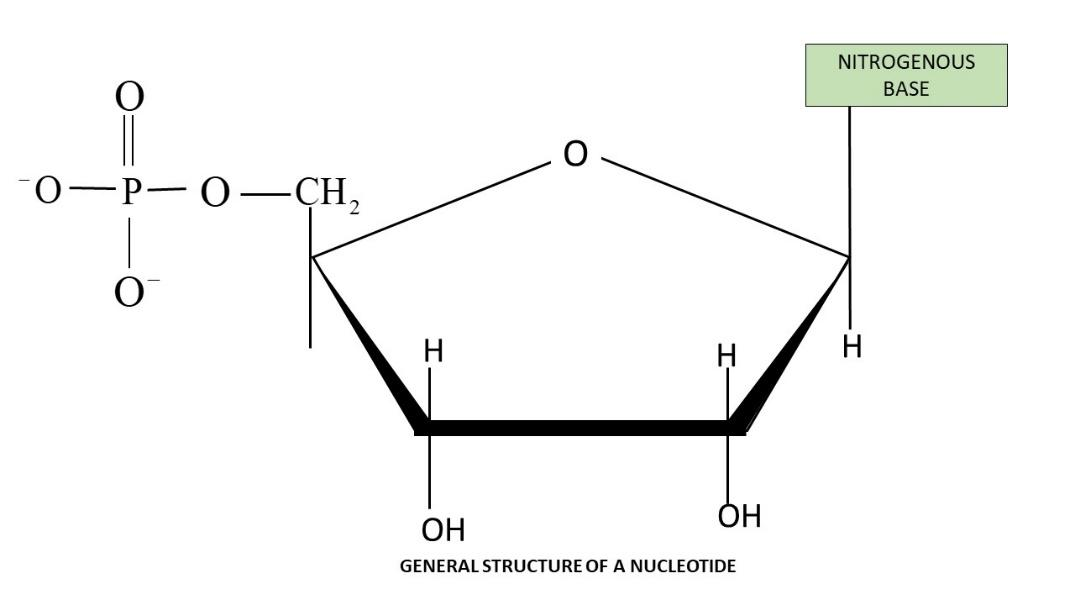

Structure of a Polynucleotide Chain

Each nucleotide is made of three components-

Nitrogenous Base

Purines- Adenine (A), Guanine (G)

Pyrimidines- Cytosine (C), Thymine (T; found in DNA), Uracil (U; found in RNA)

Sugar

Deoxyribose in DNA

Ribose in RNA

Phosphate Group

Nucleoside- Formed by linking a nitrogenous base to the 1′ carbon of the sugar (via an N-glycosidic bond).

Nucleotide- Created when a phosphate group attaches to the 5′ carbon of the nucleoside (via a phosphodiester bond).

Structure of a Nucleotide

A 3′-5′ phosphodiester bond connects two nucleotides to form a dinucleotide, and extending this same linkage builds a polynucleotide chain.

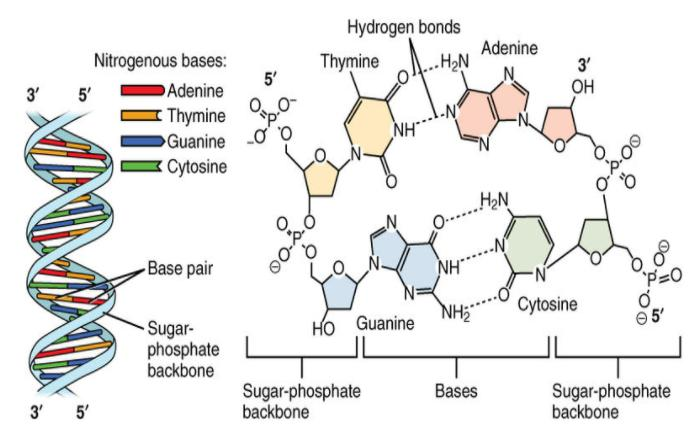

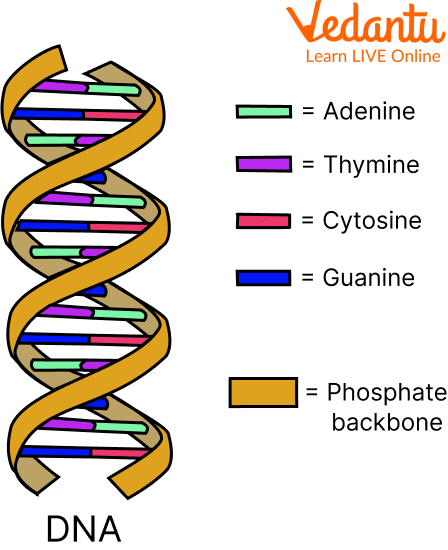

Double Helix Model for Structure of DNA

Watson and Crick (1953) proposed the double helix structure of DNA.

Ervin Chargaff discovered that the ratio of adenine to thymine and guanine to cytosine remains 1-1.

DNA is composed of two polynucleotide chains, each with a sugar-phosphate backbone.

The two strands run in opposite directions, with one in the 5′→3′ orientation and the other in the 3′→5′ orientation.

Hydrogen bonds form between nitrogenous bases on opposite strands, pairing a purine with a pyrimidine.

Adenine pairs with thymine via two hydrogen bonds, while guanine pairs with cytosine via three hydrogen bonds.

The strands coil into a right-handed helix.

Each base pair is separated by 0.34 nm, and each turn of the helix comprises 10 base pairs, resulting in a pitch of 3.4 nm.

The stacking of base pairs one above the other stabilises the structure.

Packaging of DNA Helix

In prokaryotes, DNA is organised as a large loop within the nucleoid region, where negatively charged DNA is stabilised by positively charged proteins.

In eukaryotes, DNA is densely packed into chromosomes and wraps around histone octamers (eight histone proteins) to form nucleosomes.

Histones are positively charged due to a high content of basic amino acids (lysine and arginine). The five main types of histones are H1, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4.

Each histone octamer has two copies each of four distinct histone proteins and is essential in regulating gene activity.

Nucleosomes, each containing about 200 base pairs of DNA, prevent DNA from becoming tangled.

Non-histone chromosomal proteins (NHC) further compact the chromatin structure.

Euchromatin is loosely packed, transcriptionally active DNA that appears light in staining.

Heterochromatin is tightly packed, transcriptionally inactive DNA that appears dark upon staining.

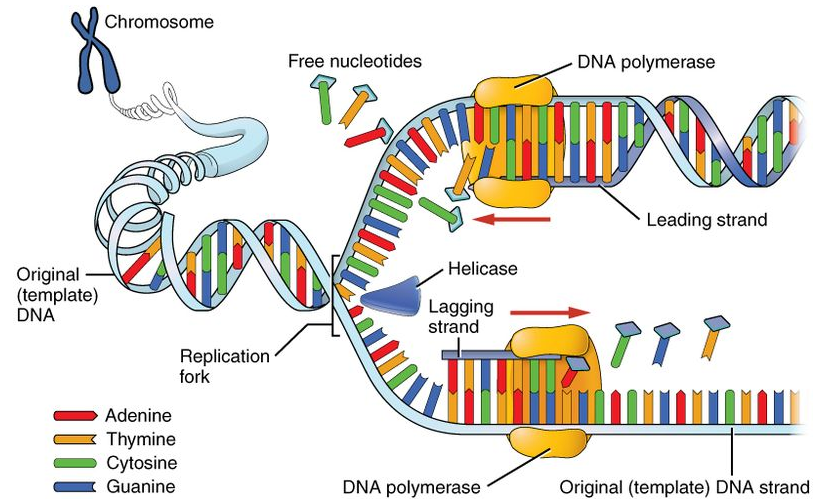

Replication

Watson and Crick proposed the semiconservative model of DNA replication.

Meselson and Stahl (1958) experimentally confirmed this semiconservative nature.

Taylor and colleagues demonstrated semiconservative replication in fava beans (Vicia faba) using radioactive thymidine.

DNA polymerase is the enzyme responsible for DNA replication and adds nucleotides only in the 5′→3′ direction.

Replication begins at specific origins of replication.

Deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates serve as both substrates and energy sources for polymerisation.

A replication fork forms when a section of DNA unwinds.

The leading strand is synthesised continuously in the 5′→3′ direction, pairing with a 3′→5′ template strand.

The lagging strand is synthesised in short segments (Okazaki fragments) due to its 5′→3′ template orientation; these fragments are joined by DNA ligase.

In eukaryotes, replication occurs during the S phase of the cell cycle.

If cell division does not follow replication, polyploidy may result.

Transcription

Definition of Transcription- The process by which genetic information in DNA is copied into RNA.

Specific Region of DNA- Only a particular segment of the DNA is transcribed at any given time.

Base Substitution- In RNA, uracil (U) replaces thymine (T) found in DNA.

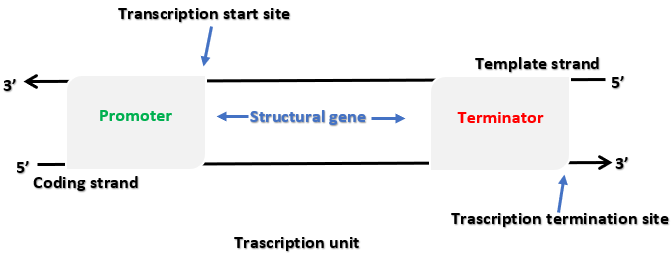

Three Main Regions- Transcription involves a promoter, a structural gene, and a terminator.

Direction of Transcription- RNA polymerase synthesises RNA in the 5′→3′ direction, similar to DNA polymerase action.

Template (Antisense) Strand- Has a 3′→5′ polarity and serves as the actual template for RNA formation.

Coding (Sense) Strand- Runs 5′→3′, matches the newly formed RNA sequence except that thymine is replaced by uracil.

Promoter- Located upstream (on the 5′ side) of the structural gene on the coding strand, where RNA polymerase binds and transcription begins.

Structural Gene- Lies between the promoter and the terminator; a cistron is a segment of DNA coding for a polypeptide. Eukaryotes typically have monocistronic genes, whereas prokaryotes can have polycistronic genes.

Terminator- Positioned at the 3′ end of the coding strand, signaling the end of transcription.

Split Genes in Eukaryotes- Eukaryotic genes are often split into exons (coding sequences retained in mature RNA) and introns (non-coding regions removed from the final processed RNA).

Transcription in Prokaryotes

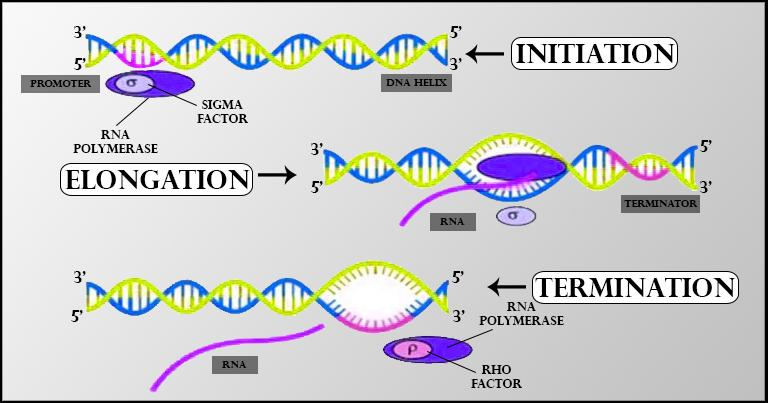

In bacteria, a single DNA-dependent RNA polymerase is responsible for producing all three types of RNA—mRNA, tRNA, and rRNA. Transcription occurs in three steps-

Initiation- RNA polymerase associates with a sigma (σ) factor at the promoter region to begin transcription.

Elongation- RNA polymerase alone carries out the elongation of the growing RNA strand.

Termination- Upon reaching the terminator region, RNA polymerase interacts with a rho (ρ) factor to end transcription, causing the newly formed RNA to detach.

Because bacteria do not have a separate nucleus and cytoplasm, the mRNA produced does not undergo further processing. Translation often begins even before the entire mRNA transcript is fully synthesised.

Transcription in Eukaryotes

Eukaryotic cells use three different RNA polymerases for transcribing various types of RNA-

RNA Polymerase I produces rRNA (28S, 18S, 5.8S).

RNA Polymerase II synthesises hnRNA (heterogeneous nuclear RNA), which is the precursor of mRNA.

RNA Polymerase III generates tRNA, 5S rRNA, and snRNA (small nuclear RNA).

The primary transcript, which includes both exons (coding regions) and introns (non-coding segments), is not functional until it undergoes-

Splicing, removing introns and joining exons in the correct order.

Capping, where a methylguanosine triphosphate cap is added at the 5′ end.

Tailing, where 200–300 adenylate residues (poly-A tail) are added at the 3′ end.

Once processing is complete, the mature mRNA is transported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm for translation.

Genetic Code

The genetic code is the sequence of bases in mRNA that specifies amino acids during protein synthesis. Each amino acid is encoded by a triplet of nucleotides known as a codon. Codons are largely universal (with a few exceptions in some protozoans and mitochondria), and more than one codon can specify the same amino acid (this redundancy is called degeneracy). Of the 64 total codons, 61 code for amino acids, while three (UAA, UAG, UGA) serve as stop codons. AUG not only signals the start of translation but also codes for methionine.

Genetic Mutations

Point Mutation- A single base-pair change, as seen in sickle cell anemia. In this condition, the normal glutamate in the β-globin chain is replaced by valine due to a point mutation.

Frameshift Mutation- Occurs when one or two base pairs are either lost or gained, altering the reading frame at the point of insertion or deletion.

Translation

Translation is the process by which amino acids are polymerised into proteins via peptide bond formation. Three types of RNA each play a distinct role-

mRNA provides the blueprint for the amino acid sequence in the new polypeptide chain.

tRNA functions as the adapter, carrying specific amino acids and recognising codons on the mRNA.

rRNA has structural and catalytic responsibilities within the ribosome.

Francis Crick’s concept of an “adapter molecule” led to the identification of tRNA (previously called sRNA). Each tRNA has an anticodon loop complementary to the codon on mRNA and an amino acid attachment site. The charging of tRNA with its respective amino acid is known as aminoacylation. Ribosomes serve as the sites where mRNA and charged tRNAs align, facilitating peptide bond formation. The process goes from the 5′ to 3′ end of the mRNA, and the ribosome can hold two tRNAs at once so their amino acids can link. A specialised 23S rRNA in bacteria (a ribozyme) catalyses the peptide bond. The coding region on mRNA is flanked by a start codon (often AUG) and a stop codon (UAA, UAG, or UGA), with untranslated regions (UTRs) at both ends that improve translation efficiency. When a release factor binds to a stop codon, the completed polypeptide is released from the ribosome.

The Central Dogma

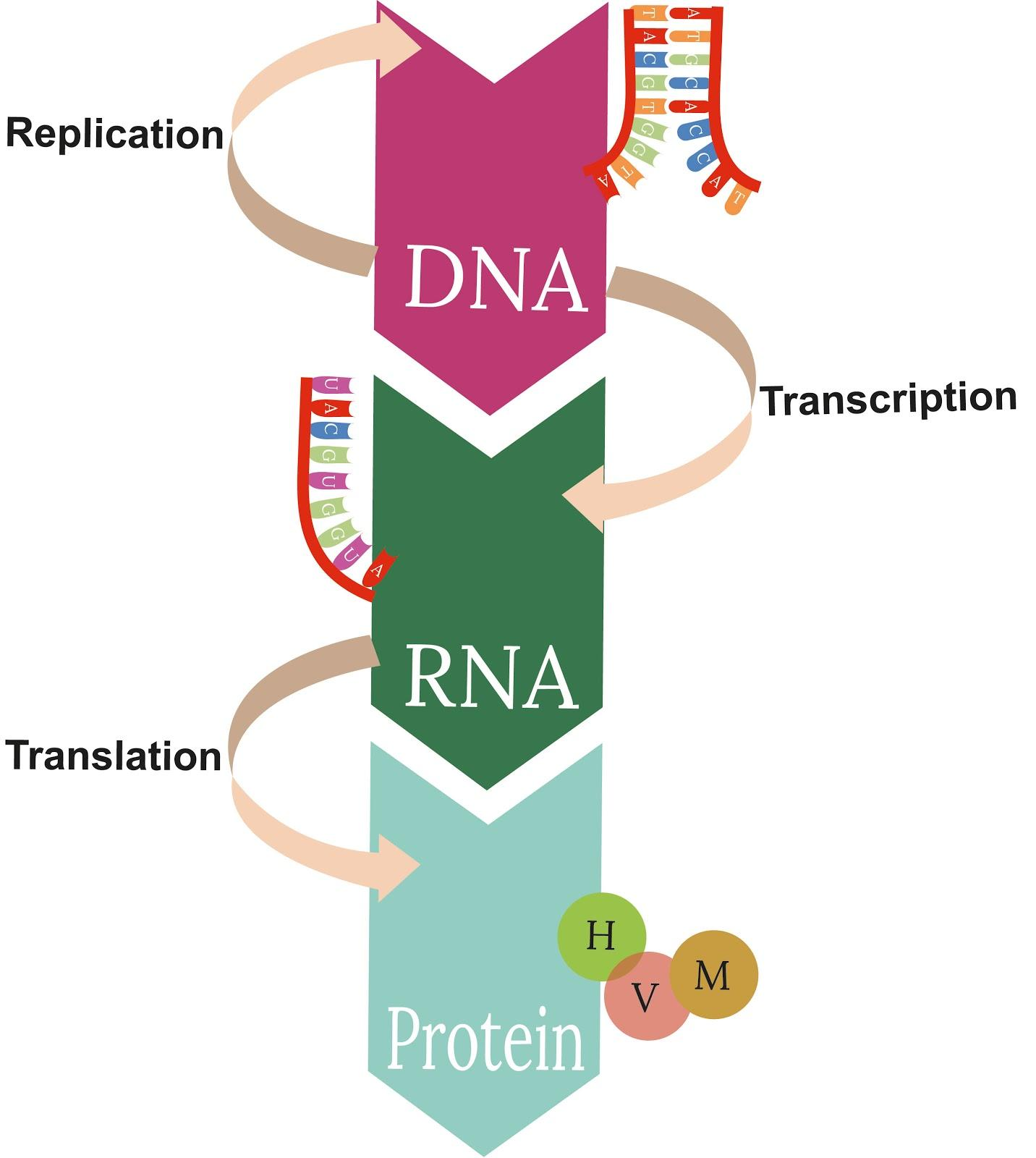

Francis Crick’s central dogma describes the unidirectional flow of genetic information- DNA → RNA → Protein.

Regulation of Gene Expression

A gene can be regulated at several stages in eukaryotes- during transcription, RNA processing (splicing), mRNA transport from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, or at the translational level. Various factors, including environmental signals and metabolic conditions, influence how much or how little a gene is expressed. In prokaryotes, gene expression is primarily controlled at transcription initiation. Regulatory proteins, serving as repressors or activators, bind to the promoter region or to an adjacent operator to modulate RNA polymerase activity.

The Lac Operon

Jacob and Monod were the first to describe a transcriptionally regulated system using the lac operon model. An operon consists of multiple structural genes under the control of a single promoter and regulatory elements. The lac operon features-

A regulatory gene (i) produces a repressor protein that binds to the operator region, blocking transcription by RNA polymerase.

Three structural genes (z, y, a) encoding β-galactosidase (splits lactose into glucose and galactose), permease (increases cell permeability to β-galactosides), and transacetylase.

Lactose (or its isomer allolactose) acts as the inducer by binding to and inactivating the repressor, allowing RNA polymerase to transcribe the operon. This form of control is known as negative regulation because it relies on the removal of a repressor to initiate transcription.

Human Genome Project (HGP)

Launched in 1990 to determine the complete sequence of human DNA, the Human Genome Project concluded in 2003 (with chromosome 1 completed by 2006). Key discoveries include-

The human genome has about 3.1647 billion base pairs.

Around 30,000 genes exist, with an average size of 3,000 bases per gene.

The largest known human gene is dystrophin, at 2.4 million bases.

99.9% of all human DNA is identical across individuals.

Only about 2% of the genome codes for proteins.

Chromosome 1 contains the highest number of genes (~2968), while the Y chromosome has the fewest (~231).

Approximately 1.4 million sites have single-base differences (SNPs, or single nucleotide polymorphisms).

DNA Fingerprinting

Originally developed by Alec Jeffreys (using Variable Number of Tandem Repeats, VNTR), DNA fingerprinting exploits differences in the DNA sequence between individuals. It focuses on repetitive DNA regions called “satellite DNA.” These do not code for proteins but are highly variable, making them useful for identity verification, paternity testing, and forensic investigations. Such polymorphic repeats are inherited, allowing DNA fingerprinting to detect genetic diversity within populations and confirm family relationships.

Essential Study Materials for NEET UG Success

FAQs on Molecular Basis of Inheritance- Important Notes for NEET Biology

1. What is the Central Dogma of Molecular Biology?

The Central Dogma states that genetic information flows from DNA to RNA and then to proteins. In other words, DNA is transcribed into RNA, which is then translated into a polypeptide (protein).

2. How does DNA Replication differ between the leading and lagging strands?

During replication, the leading strand is synthesised continuously in the 5′→3′ direction. The lagging strand, however, is synthesised in short segments called Okazaki fragments because its template runs in the opposite direction (3′→5′), requiring periodic re-initiation of synthesis.

3. Why is the Lac Operon important in Molecular Biology?

The lac operon is a model for understanding gene regulation in prokaryotes. It demonstrates how genes for lactose metabolism in E. coli are turned on or off depending on the presence or absence of lactose.

4. What is the significance of Chargaff’s Rule?

Chargaff’s Rule states that in a DNA molecule, the amount of adenine (A) equals thymine (T), and the amount of guanine (G) equals cytosine (C). This helped Watson and Crick deduce the double helix structure of DNA.

5. What are Exons and Introns in Eukaryotic Genes?

Exons are the coding regions of a gene retained in mature mRNA, whereas introns are non-coding segments removed during RNA splicing. Only exons are translated into proteins.

6. How do Point Mutations and Frameshift Mutations differ?

A point mutation affects a single nucleotide base (e.g., substituting one base for another). A frameshift mutation occurs when one or two nucleotides are inserted or deleted, altering the reading frame and drastically changing the resulting protein.

7. What is DNA Fingerprinting used for?

DNA fingerprinting identifies unique repetitive (satellite) DNA sequences in individuals. It is commonly used for forensic investigations, paternity tests, and studying genetic diversity.

8. What is the difference between Euchromatin and Heterochromatin?

Euchromatin is lightly packed, transcriptionally active DNA (appears lighter under a microscope), while heterochromatin is densely packed, transcriptionally inactive DNA (stains more darkly).

9. What role does RNA Polymerase play in Transcription?

RNA polymerase binds to the promoter region of a gene, unwinds the DNA strands, and synthesises RNA in the 5′→3′ direction using the DNA template strand.

10. Why are Okazaki Fragments formed on the Lagging Strand?

Because DNA polymerase can only synthesise in the 5′→3′ direction, it must work in short bursts on the lagging strand, resulting in short DNA pieces (Okazaki fragments) that are later joined by DNA ligase.